The Nifoula

The Nifoula

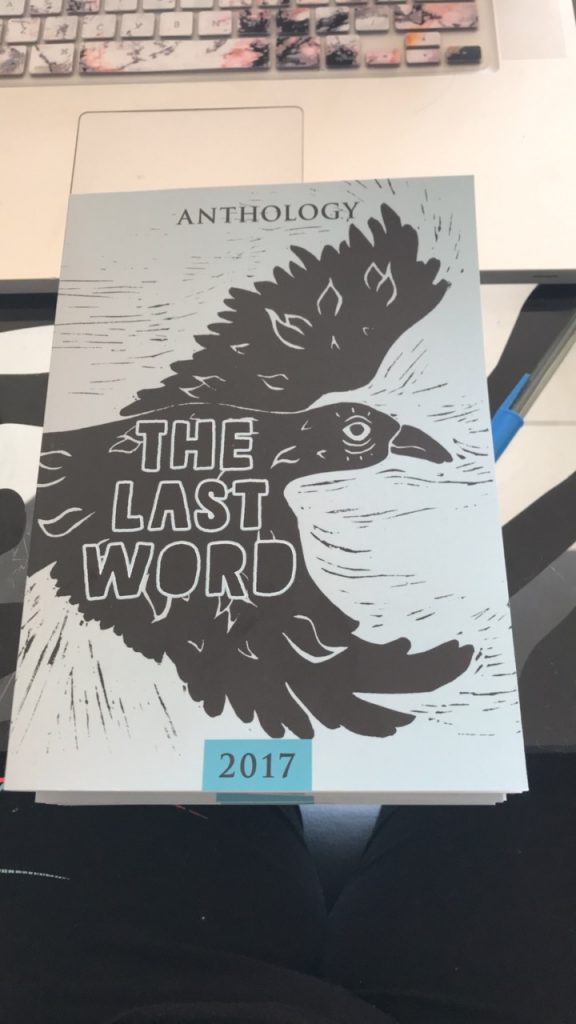

As printed in The Last Word Anthology, you can find a copy of it here

Long drives, open roads and old school Greek beats are prized possessions in the memories of my childhood. The purring of the V8 engine of Dad’s cherished ‘71 Holden Brougham, lovingly nicknamed The Nifi, because he adored the car like a wife, vibrating through my brain like a song I can’t seem to forget, nor do I want to. After the death of my dad, these memories are worshipped above all else. The tune of Mikri Mou Melissa, a song that always recalls images of tapping on the slim steering wheel, while singing loudly off tune, is a melody that encores rose coloured memories in my life.

Most would bemoan a three-hour car ride to Berri to visit their god sister, or the eight-hour drive to Melbourne from my old suburb of Edwardstown in Adelaide, but not me. Instead of enjoying the luxury of having an entire backseat to myself as a child, I pestered my parents with cries of ‘are we there yet?’ and a never ending supply of bounding energy that had me leaning forward to annoy them. Memories of relishing the bucket seat all to myself while my brother, Peter, was too young to sit at the back without a seatbelt are lost on me. Before you start to panic, cars manufactured before 1975 without a seatbelt legally didn’t need one. Dad fitted a middle seat belt at the front and back as a safeguard for us while we were too rambunctious to be trusted without one. My brother soon grew up and joined me in the back seat, where I lost my freedom to move.

As I discovered my love of books, car rides became a chance to read those gloriously penned works of art, mostly without disruption. We would stop to stretch our legs half way and eat ham and cheese rolls, hot chips and drink coke. The public toilets carried the fear of finding spiders, because this naïve city girl had no trust in country towns.

Just the mention of a car ride caused excitement for the chance to get the car ready for what was to come. You see, there were different materials needed depending on the season, because preparation for long trips would make or break the journey.

In summer, it involved strategically threading a sheet through a small crack in the wound down window, and closing it fast enough so that it would catch a neat row of fabric in one go. There was a skill in getting the timing just right, and my brother and I never thought to ask each other for help.

In winter, it required blankets. Lots of them. Because The Nifi was Dad’s pride and joy, we had to lay a barrier down as a preventative measure. The blanket, a single blue polyester blend, was expertly tucked into the join between the seat to protect the beige floral fabric from prospective coke spillage, possible vomit, food dropage and pen marks. It didn’t work to stop the pen marks. Sorry, Dad.

And, just as with any good car trip, it always needed pillows. Peter and I would push our pillows against the doors, our Discman’s resting on our bellies and limbs strategically stretched out. One set of legs against the side of the bucket seat and the other on the outside. After some time we would switch to regain mobility in our limbs.

As various birthdays, weddings and christenings cropped up, our team of four would sometimes extend to a team of ten. My two cousins, uncle and auntie, and grandparents joining our ranks.

Squishing ten people into two cars was always a bit challenging. The lack of wriggle space to move for such prolonged periods of time was enough to make anyone crazy, a fact we tempered by dividing my grandparents between the two cars. My cousins got Yiayia while we got Pappou. He always added his jokes to the car and would join in on the singing; I always thought that we got the better grandparent out of the two, but I’ll never admit it to Yiayia.

With a fifth person in the car, it meant that Mum was squished at the back with Peter and I. Stretching out became an impossible game.

We would crane our neck to see where our cousins were, their red car a staple in our life. Waving and pulling faces from our car would entertain us for three quarters of the trip – the other quarter was spent nursing the sore necks it caused.

We grew up on the road and it’s no surprise that when a stress or situation crops up, the first thing my brother and I crave is a car trip.

Maybe it’s the purring of the engine, the loud tunes or the way the wind whips around the car as we put the pedal to the metal that soothes us, but there’s a magic in being able to settle a busy mind.

One of the last trips I made with Dad was when he helped me move from Adelaide to Melbourne to start my new life. I was only half familiar with the big city; another story for another day, but I will say that the Nifi broke down in Tintinara and added two and a half hours to our trip. It was almost a solo journey, because I spent the first two hours mad at him for what now seems pointless, but the open road and the witty banter with the mechanic that fixed the car was enough to switch the gears up. Mikri Mou Melissaki was played after we resumed talking and laughing.

The hole that Dad’s death leaves in my heart is like an unfinished symphony that leaves me longing for the open road and craving the mix tape that defined my childhood. And as the maestro is no longer around to sit behind the wheel of his cherished possession, it seems fitting that there is a hint of fear and absolute joy in being able to slip behind the wheel. To adjust the bucket seats and turn the key in the ignition and hear the engine purr. To take his place and carry on his legacy. Making the open road our meditative playground once again.

Feel free to leave a memory that you have with yoru relatives, dead or alive. I’d love to hear all about them in the comments below.